What is Maestro?

Maestro is a coordination layer that promotes agnostic design while allowing for communication between its varying components, even if those components are designed as isolated features.

There are two core components to the framework (discussed below); modules and services.

Modules build the UI, Services coordinate the data.

Modules & Services expose certain bits of information and functionality; however, with Maestro those implementations are agnostic.

What it Isn't

Maestro is not a data flow or design pattern. It is a agnostic coordination layer.

In fact, Maestro will work with any design pattern you choose to implement; whether BLoC, MVVM, MVP or Clean Architecture.

You can use BLoC directly in a Maestro Module, or extend the Maestro Module to bring in full BLoC functionality!

This is possible because Maestro is written in (nearly) pure Dart/Flutter and is intended for use at a lower level than your design pattern.

Getting Started

Maestro Application

The Maestro Application class is the base of the framework and acts as the coordinator.

Instantiating:

Application application = Application();

The Application is a static singleton, and can be accessed directly; however, the recommendation is to wrap the application in an AppWidget using App.create():

runApp( App.create(

application: application,

initialRoute: '',

));

App.create accomplishes the following:

- Provides Application in a familiar way, through the use of an Inherited Widget:

Application.of( context );

- Allows setting SystemUiOverlayStyle properties via the Application view model.

- e.g.

application.viewModel.statusBarBrightness.value = Brightness.dark;

- e.g.

- Allows setting AppBar, BottomSheet and BottomNavigation at a global level.

Application.of( context ).setAppBar( {Any Widget} );

We must register our dependencies with the Application so that it knows how to route and behave.

e.g.

// Registers MyModule

application.register( MyModule( application ) );

Modules (and its counterparts) are discussed in detail further down in this guide.

Whenever a dependency is needed, it is requested from the Application. e.g.

// Returns MyModule instance.

application.component<MyModule>();

It is also possible to see if a component exists before grabbing it:

application.componentExists<MyModule>();

Components

Components are the building blocks of a Maestro app, and should be designed as isolated as possible.

There are two core components: Modules and Services.

Before we dive into those components, lets first talk UseCase!

UseCases

Maestro contains a semi-agnostic UseCase framework. Separate Repository

A UseCase is a component which contains business rules/business logic.

Used commonly in Clean Architecture, UseCases allow for further abstraction and reusability of business logic.

There should be absolutely no dependencies on the view in a UseCase.

With Maestro, once a UseCase is registered, it can be used anywhere. You can think of it like an exported function. The caller doesn't know anything about the function, but is allowed to utilize it.

UseCases should be lightweight and perform the smallest amount of work necessary to accomplish its task, and not expose how it works.

Here is an example UseCase:

class LoggingUseCase extends UseCase {

@override

String get id => Maestro.useCases.globalLoggingUseCase;

LoggingUseCase();

@override

FutureOr<void> execute( Map<String, dynamic>? args ) async {

if ( args != null && args.containsKey('message') ) {

print( 'Maestro Log: ${args['message']}' );

}

}

}

This example shows a UseCase that just prints a log message. This could be useful if you wanted to abstract a certain logging library. There would be no dependency on that library and if you ever wanted to swap it out for another, the change would only need to happen in one place (the UseCase!).

UseCases can be called directly:

LoggingUseCase luc = LoggingUseCase();

luc.execute( { 'message': 'Hi!' } )

However, that is not recommended because you now have a hard dependency on the UseCase.

The recommended approach is to register your UseCase with the application. Doing this will expose it to all Modules and Services, without forcing them to depend on it.

The UseCase is identified only by a unique string. Maestro can generate unique IDs for UseCases via maestro_builder. More on that later!

// luc.id => 'loggingUseCaseUniqueID'

LoggingUseCase luc = LoggingUseCase();

application.registerUseCase( luc );

There are multiple ways to execute a UseCase once registered, and doing so will add it to a queue.

Maestro iterates that queue and fires each queued UseCase asynchronously.

Each UseCase has its own state, which is one of the following:

none - UseCase is not being managed.

queued - UseCase is in the queue and will be executed.

started - UseCase execution has started. waiting - Waiting for UseCase to finish.

done - UseCase finished with success.

error - UseCase finished with errors.

All UseCase statuses are kept in memory until the queue has been depleted.

If you fire the same UseCase with equal arguments twice during a queue traversal, the observers are joined. This means the UseCase only fires once but both observers are notified of the status (state & value).

You can execute a without needing the response:

application.callUseCase( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase );

Or with a handler:

application.callUseCase( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase, observer: UseCaseHandler(

onUpdate: ( status ) { ... }

) );

A use case can also be converted into a future:

dynamic x = await application.callUseCaseFuture( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase );

or a stream:

Stream<dynamic> x = await application.callUseCaseStream( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase );

The UseCase will execute when a listener attaches to the stream. When the UseCase completes, the stream is closed.

You can also turn any Class (e.g. a BLoC) into an observer, and pass it to the call method:

class MyBloc extends Bloc implements UseCaseObserver {

const MyBloc();

@override

void onUseCaseUpdate(UseCaseStatus update) {

print('MyBloc : ${update.state}');

}

}

Finally, you can subscribe to a specific UseCase:

class MyBloc extends Bloc implements UseCaseObserver {

final Application application;

late final UseCaseSubscription subs;

MyBloc( this.application ) {

subs = application.subscribe( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase , this );

}

void init() {

application.callUseCase( Maestro.useCases.loggingUseCase );

}

void dispose() {

subs.dispose();

}

@override

void onUseCaseUpdate(UseCaseStatus update) {

print('MyBloc : ${update.state}');

}

}

In the example above, onCaseUpdate will fire whenever the logging use case executes, no matter who executed it or what parameters were passed in.

Always call dispose on the returned UseCaseSubscription.

Modules

Modules contain the UI layer, and should not be hard dependencies of each other (there is no need!).

Modules can access the data layer through Services; which can be depended on; however.

They also contain routes, slices and use-cases; all of which can be exposed to other Components.

To create a Module, extend the Module class and add the singleton constructor:

Example:

class MyModule extends Module {

static MyModule? instance;

MyModule._(Application application) : super(

application: application,

);

factory MyModule([ Application? application ]) {

assert( instance != null || application != null );

return instance ??= MyModule._(application!);

}

}

At this point, you are able to register MyModule with Maestro. Add this line where you instantiated the Application.

application.register( MyModule( application ) );

This won't actually do anything though, because we have not told the application what the module exposes.

To do that, update your MaestroApp annotation:

@FrameworkApp(

modules: [

MyModule,

],

)

Once that is done, go ahead and annotate your module with MaestroModule, telling the Application which routes you are going to expose:

@MaestroModule(

baseRoute: 'my_route',

childRoutes: [

'landing',

],

)

class MyModule extends Module { ... }

In this example, we are informing the application about the routes that this module can handle. The base route is my_route, which exposes a single childRoute named 'landing.'

In short, we are simply exposing routes, allowing one module to directly route to another.

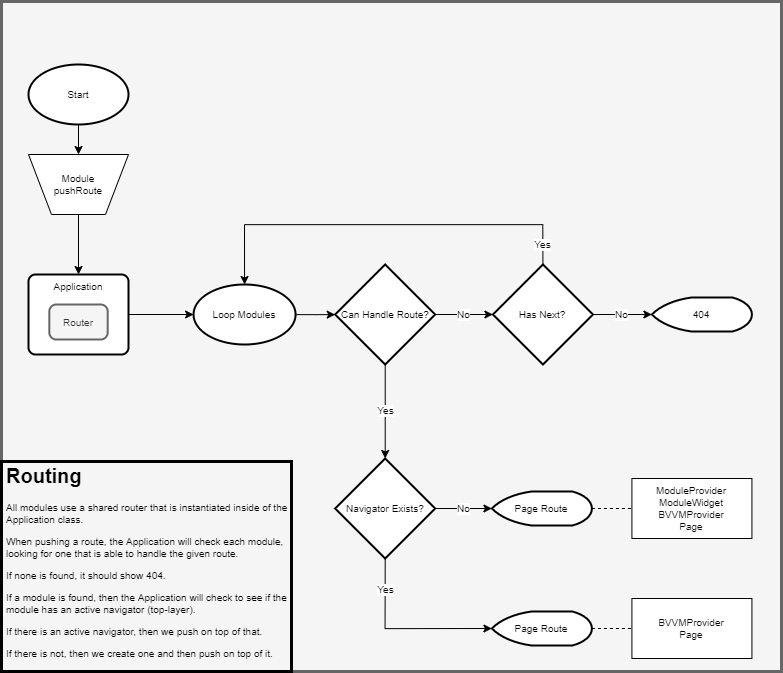

Routing

Routing is handled inside of Maestro; however, it uses the basic Flutter navigator. That means that you should be able to use Maestro routing with other packages such as Modular, should that be desired.

To enable routing between Modules without introducing a hard dependency, we can use maestro_builder code generation.

Maestro_Builder

Make sure to always run build_runner after updating annotations:

flutter pub run build_runner build --delete-conflicting-outputs

After running build_runner, you should see a part file that contains your exposed route name:

// ********************************

// Maestro Routes

// ********************************

class _Routes {

const _Routes();

final String myModuleMyRoute = '/my_route/landing';

}

You are now able to route to your module from any registered Module, without requiring a hard dependency.

application.router.pushNamed( Maestro.routes.myModuleMyRoute , arguments: {} );

The application router is just a wrapper for pure Flutter navigators. The application has a navigator, as does each Module.

When you pushNamed, the application will check to see if there are any modules that can handle the route. If not module exists, then you will land on a 404.

Here is the logical flow for routing:

Popping a route is essentially the same, except the application determines which module is currently in use. If it can pop, then the module navigator handles it. If it cannot pop, the module is popped off the navigation stack, exposing the module underneath of it.